The BFF Pattern: Friendship Goals for Frontend and Backend

It started, like many good architecture ideas, in a meeting room filled with slightly annoyed stakeholders. Marketing was upset because the mobile app was slow to load. The web team couldn’t keep up with changes to the backend. Product complained that adding features to the TV app required weeks of cross-team coordination. And the backend engineers? They were juggling a monolithic API surface area that had grown into a forest of conditional logic, request filtering, and over-fetching madness.

That’s when someone said:

“Why don’t we build a backend that’s just for the mobile app?”

That was the first step into the Backend for Frontends (BFF) pattern: a practical solution that didn’t emerge from books or academic models, but from the very real frustrations and constraints faced in modern software delivery.

Why Single Backend APIs Can Cause Problems

At first glance, using a single, shared API for all frontend clients may seem efficient. However, this one-size-fits-all approach can quickly run into issues. Web applications, mobile apps, and smartwatches all operate under different conditions. They have unique expectations for data shape, latency, bandwidth, and interaction models.

Trying to serve all of them through one backend forces compromises, because a single API cannot meet every client’s needs equally well. As new devices and platforms are added, the backend becomes overloaded with conditionals, feature flags, and format adjustments. Over time, this shared API turns into a bottleneck that is hard to evolve and even harder to optimize for individual experiences:

- Mobile apps often receive too much data or data in formats that aren't efficient for low-bandwidth or limited-processing environments.

- Frontends are burdened with transforming and filtering data, introducing duplication of effort and inconsistent logic.

- Backend teams get overwhelmed managing feature requests from multiple frontend teams, creating delays.

- Changes intended for one client may unintentionally affect others, making evolution risky and coordination slow.

These problems cause delays, make it harder to deliver fast, and hurt the user experience, especially when different platforms all try to use the same API in their own way.

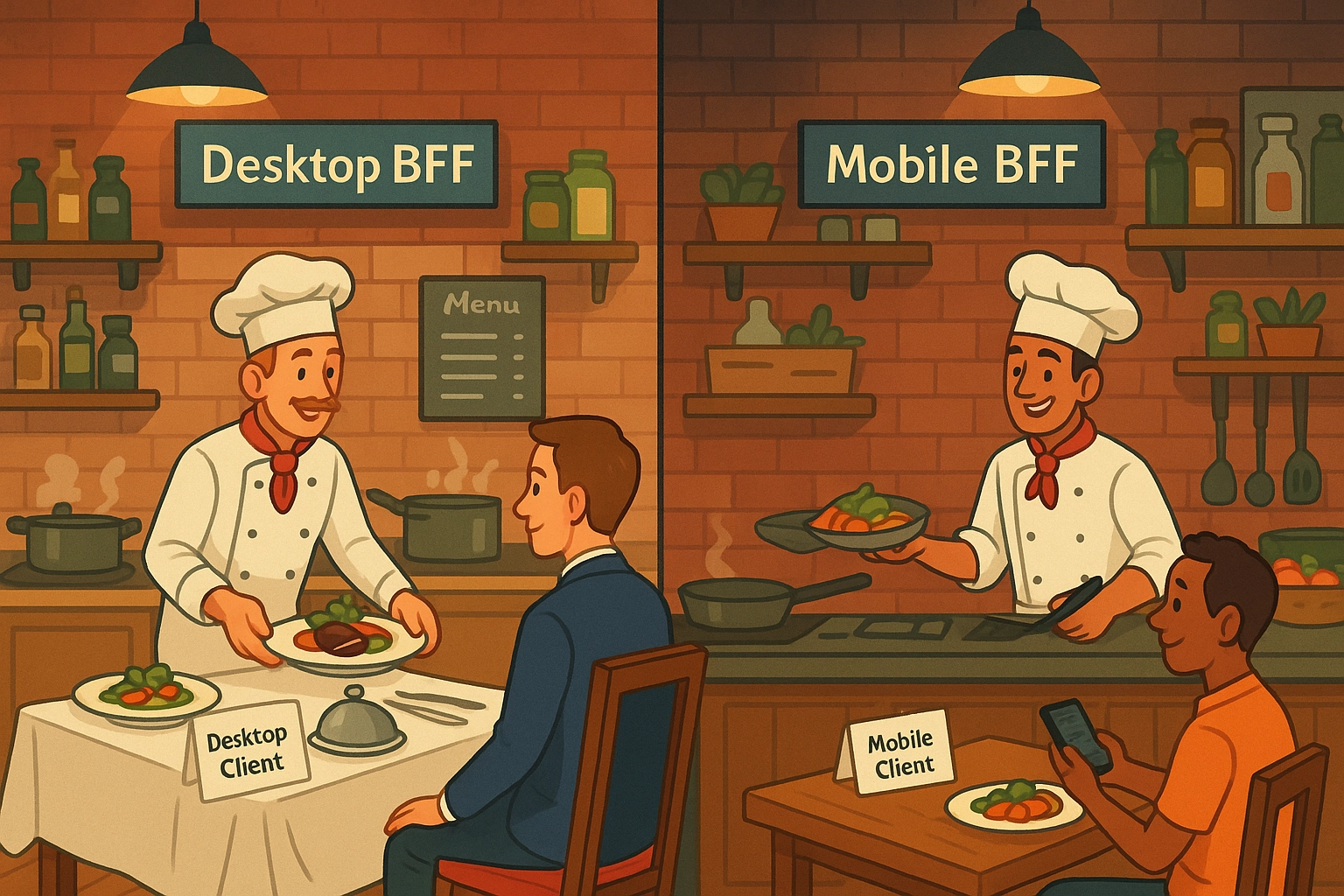

A Backend for Each Frontend

This is where the Backend for Frontends (BFF) approach comes in. Instead of trying to serve all frontends with the same generic backend, you introduce a separate backend service for each type of client. This dedicated backend is designed specifically to match the needs of that frontend, whether it's mobile, web, or any other channel.

Each BFF becomes a tailor-made API facade, optimized for the device, user journey, and performance characteristics of its target client. It can aggregate responses across microservices, shape the data exactly as the client expects, and handle logic that would otherwise bloat the frontend code. This keeps the backend clean and the frontend lean.

It also allows different frontend teams to iterate independently, without being blocked by a shared release cadence or risking regressions in other channels. The result is faster delivery, clearer responsibilities, and an architecture that embraces diversity in user experience.

How to Apply the BFF Pattern

If you're thinking of applying the BFF pattern, there are a few practical design considerations to keep in mind. Sam Newman's guidance offers valuable architectural thinking on when and how to implement this effectively:

1. Design BFFs Around User Experience, Not Just Devices

While BFFs are often aligned with device types (e.g., mobile, web), it’s better to think in terms of user experience boundaries. For example, a single web application might serve vastly different user personas, such as customers, partners, and administrators, each with different interaction needs and expectations. By designing BFFs around these distinct user journeys instead of just the device, you can better align data shaping, business logic, and performance to the context in which the user operates. This makes it easier to decouple complexity and improve clarity in both frontend and backend code.

2. Keep BFFs Focused and Disposable

BFFs should be lightweight, focused, and easy to rebuild. They are tactical tools designed to serve a specific frontend interface, not permanent backend infrastructure. Keeping their scope narrow reduces the risk of architectural sprawl. If a BFF starts accumulating too much responsibility, that's a signal to reevaluate and possibly break it up. The ideal BFF can be retired or rewritten quickly without major disruptions, making them a safe space for innovation and iteration.

3. BFFs Should Be Owned by the Frontend Team

To avoid handoff delays and siloed development, the team responsible for the frontend should also own its corresponding BFF. This co-ownership ensures that changes to frontend requirements are reflected quickly in the BFF, without waiting on backend roadmaps. It encourages shared accountability, improves development velocity, and keeps the API surface tightly aligned with user experience goals. When frontend and BFF evolve together, teams can ship features faster and more reliably.

4. Watch for Duplication and Drift

One risk of using multiple BFFs is the duplication of logic and divergence in how backend services are represented. Over time, similar logic implemented separately in different BFFs can cause maintenance overhead and inconsistencies. Be deliberate about what should live in shared libraries versus what belongs inside the BFF. Consider aligning service contracts and centralizing common transformations to reduce unnecessary variance. Consistency, when appropriate, enhances reliability and reduces onboarding time for new developers.

5. Consider Gateway Patterns for Cross-Cutting Concerns

If you find yourself duplicating logic such as authentication, authorization, logging, or caching across multiple BFFs, it might be time to introduce a shared API gateway or middleware layer. These cross-cutting concerns are better handled centrally to ensure consistency, reduce boilerplate, and make it easier to apply policies. A gateway can also handle tasks like rate limiting, request throttling, and security enforcement, freeing BFFs to focus purely on client-specific needs.

6. Know When Not to Use a BFF

The BFF pattern isn’t always the right fit. If your application serves only one type of frontend or if all clients can already use a flexible interface like GraphQL or OData, introducing a BFF might be unnecessary overhead. Similarly, if your frontend team has limited resources or the product is still in early validation stages, the added layer may slow things down. Use the BFF pattern when it simplifies integration and accelerates delivery, not when it adds complexity or duplication.

Delivering Tailored Experiences with Purpose

The Backend for Frontends pattern is about designing with clear intent. It addresses the fundamental challenge of building fast, responsive, and scalable frontends in a world where users expect seamless experiences across devices. By giving each frontend a backend that understands its context, its user journey, platform constraints, and team workflow, we reduce friction in delivery and empower teams to move faster with confidence.

You avoid the slowdowns of shared APIs, prevent accidental regressions, and enable domain-focused evolution. When teams own both the frontend and its dedicated BFF, they can experiment, iterate, and deploy independently without stepping on each other’s toes. The BFF pattern helps solution architects balance two critical forces: frontend agility and backend stability. It’s not a silver bullet, but when applied where it fits, it can turn a fragile architecture into a flexible one.