Architect and Stakeholders: Power, Interest, and the Unseen Architecture

Every solution architect knows that systems aren't the only things with dependencies, people are too. The APIs we integrate are predictable. Stakeholders? Not so much. You're mapping domains, aligning systems to business capabilities, wrestling with legacy constraints, and just when you think you've nailed the architecture, a sponsor with high power and low interest torpedoes your roadmap with a casual "I don't see the value."

Sound familiar? Stakeholder management isn't a soft skill, it's a survival skill. And if you've ever wondered why your cleanest architectures still struggle to get buy-in, it's probably because you missed the invisible architecture: the power-interest landscape.

Why Stakeholders Are Architecture, Too

Stakeholder management isn't a peripheral task, it's a core architectural concern, recognizing that architecture must serve, influence, and be influenced by people who hold varied agendas, authority levels, and attention spans. Whether you're working on cloud migration, standing up a new service mesh, or rethinking enterprise identity, your success lives and dies on this one thing: alignment. Alignment doesn't just mean across systems, it means across stakeholders.

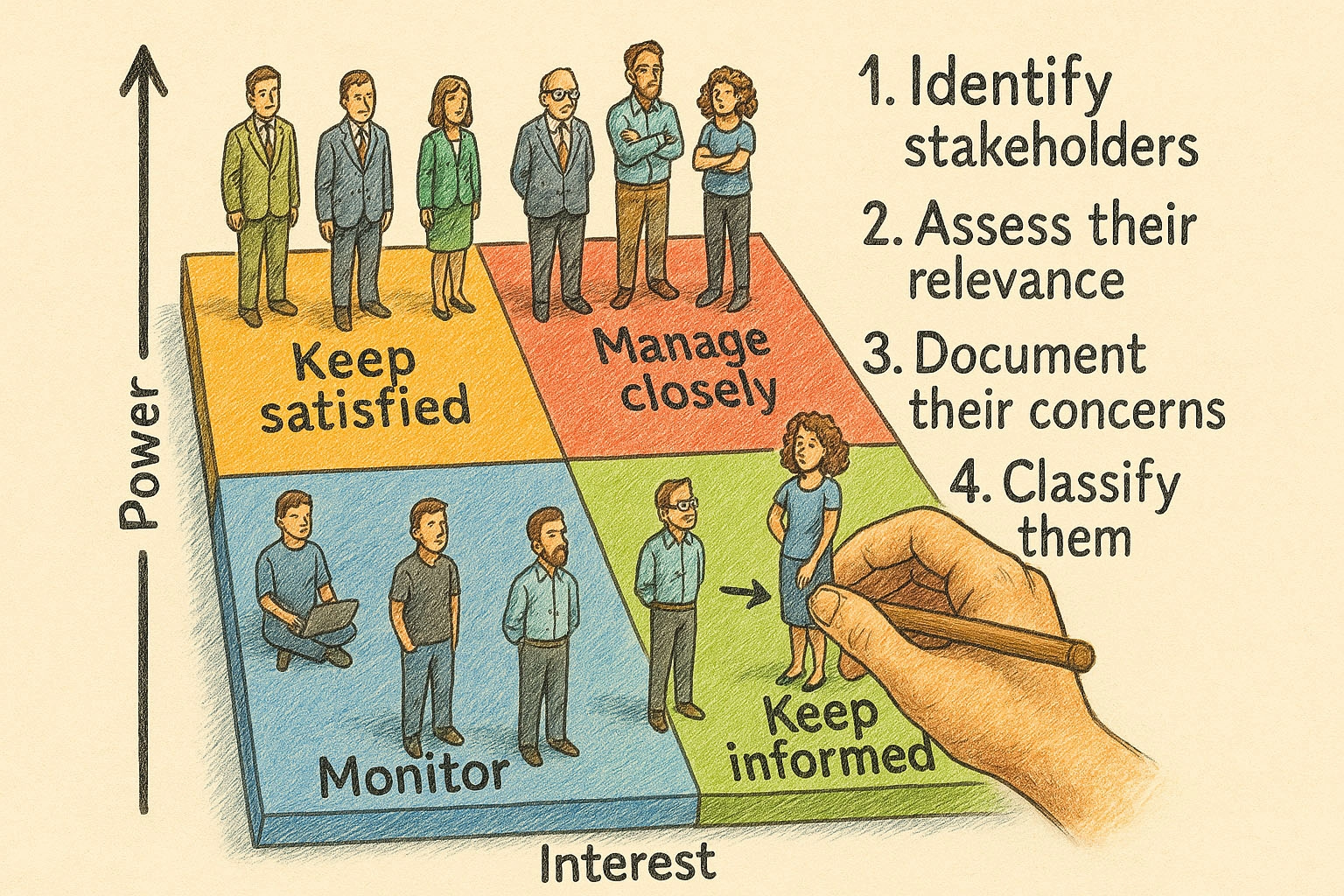

That's why stakeholder management calls for a structured approach: identify stakeholders, assess their relevance, document their concerns, and classify them. But one framework cuts through the noise with elegant simplicity: the power-interest matrix.

Enter the Power-Interest Matrix

Once you've identified your stakeholders, the next question becomes: how do you engage them effectively? This is where the Power-Interest Matrix earns its place as one of the most practical tools in a solution architect’s arsenal. It tells you not just who matters, but how to work with them.

Each quadrant comes with its own engagement strategy, and typical personas you’ll run into across transformation programs:

🟥 High Power / High Interest: Manage Closely

These stakeholders are deeply invested and have the authority to drive or derail your architecture. Actively manage and involve them in major decisions. Show how the architecture supports their strategic goals. Example stakeholders are Program Sponsor or Business Owner, Head of Architecture / Chief Architect, VP of Product or Engineering, and Domain Business Lead (e.g., Head of Digital Channels in a bank)

🟨 High Power / Low Interest: Keep Satisfied

They can influence outcomes significantly, but they’re not involved in the technical trenches. Engage wisely, they’re not watching until they are. Provide high-level updates and anticipate their concerns. Don’t drown them in detail, but give them confidence in governance, risk mitigation, and value delivery. Example stakeholders are CFO (concerned with cost), CISO (concerned with compliance), CIO (if not directly involved in the initiative), and Legal / Risk Officers.

🟩 Low Power/ High Interest: Keep Informed

These are your allies on the ground. They care deeply and can be your best champions, even if they don’t sign off on budgets. Communicate frequently and involve them in design sessions. Make them feel heard. They’re often the ones who spot gaps early. Example stakeholders are Product Owners, Business Analysts, Infrastructure/Network SMEs, DevOps Engineers, and Service Operations Leads.

🟦 Low Power / Low Interest: Monitor

They’re on the periphery. You don’t need to over-invest, but don’t ignore them entirely. Keep communication light and non-intrusive. Check in occasionally to ensure alignment or detect latent concerns. Example stakeholders are Admin Support Functions, Non-critical vendors, Training Teams (early stages), and Internal Audit (pre-engagement phase).

Stakeholder profiles evolve. The Keep Informed DevOps engineer might become a Manage Closely DevOps engineer during deployment. The Keep Satisfied CISO may suddenly become deeply Interested if the architecture touches on sensitive data flows. That’s why the Power-Interest Matrix isn’t a one-and-done activity. It should evolve alongside your architecture roadmap. Reassess it at every phase gate. Let it inform your stakeholder engagement strategy as much as your system design.

A Real-World Story: The Retail Reinvention

A large retail organization launched an initiative to rebuild its e-commerce platform. The new architecture was modern: headless commerce, event-driven microservices, and a flexible checkout orchestration layer that could support both online and in-store use cases.

The architecture was solid. The APIs are clean. The roadmap is realistic. But there was one critical oversight: the store operations team. They were classified as low power, low interest. After all, the architecture was about digital transformation, right? Wrong.

Halfway through the rollout, in-store pilots began. The new checkout APIs introduced latency that, while acceptable online, caused issues with the POS systems during peak hours. Store ops flagged the issue, but the architecture team had no line of communication or feedback loop set up. The result? Escalations. Delays. Emergency patches. And a tarnished rollout.

Once the operations lead was recognized as high interest, moderate power, and pulled into roadmap reviews, things smoothed out. But the damage to trust and timeline was already done.

What the Matrix Reveals (That Org Charts Don’t)

Power isn’t about job titles. Influence can come from tenure, informal networks, or control over budgets and timelines. Interest isn’t fixed. A stakeholder uninterested today may become highly engaged once real-world impact emerges. Revisit the map frequently. Communication should match the quadrant. Key players want a strategy. Keep-informed groups want clarity. Satisfied stakeholders want predictability. Don’t mix the messages. Most importantly: ignoring a quadrant isn't safe. Every quadrant can derail your momentum if not managed thoughtfully.

Make It a Living Artifact

Just like threat models, domain diagrams, and capability maps, your stakeholder map should live, evolve, and drive action.

- Kick off with it: Identify stakeholders before architecture work begins.

- Use it to drive communications: Who gets deep dives? Who gets exec summaries?

- Update it per milestone: As the solution matures, so will the power-interest balance. Make it part of retrospectives: Ask what shifted and why.

A well-maintained matrix becomes a navigation tool, helping you avoid misalignment, preempt resistance, and accelerate decisions.

Build Alliances, Not Just Architectures

Great architecture doesn’t live in diagrams, it lives in adoption, usage, and long-term value. And none of that happens without the humans behind the systems. When you treat stakeholder dynamics as an architectural input, not an afterthought, you begin to see the full picture. Not just how services talk to each other, but how people do. Where friction lives. Where trust needs to be designed.

The Power-Interest Matrix won’t solve every political wrinkle. But it will give you a lens, a way to see beyond roles and into realities. Behind every successful architecture is not just good design but the right people, aligned at the right time.